[A brief excerpt from the text "(and i can't stress this enough) in my mouth: Extradiegetic Affect as Material", a long-form essay that proposes cinema’s likeness to the ecological circulation of microplastics -- a claim made to illustrate cinema’s materiality and nearly invisible ubiquity. The notion of "extradiegetic affect" is outlined as a post-cinematic condition in which lived experience becomes secondary to cinematic representation and which, simultaneously, becomes directly shaped by engaging with these representations.]

The bodies we call “Tom Hanks” and “Meg Ryan” can be seen falling in love in four major motion pictures between the years 1990 and 2016. This realization can trigger a series of mad questions. The first dots to connect elicit casual amusement: You’ve Got Mail (1998, dir. Nora Ephron) and Sleepless in Seattle (1993, dir. Nora Ephron) as equally iconic snapshots of the general stability experienced by white professionals in the US between global economic depressions, or perhaps between AIDS and 9/11. That each work falls within Nora Ephron’s RomCom canon certainly connects the two as well, but the discovery of Joe versus the Volcano (1990, dir. John Shanley) is more surreal, bringing these instances of avatar resonance towards a dazed equilibrium. The latest introduction of Ithaca (2016, dir. Meg Ryan) ties a knot in this rhythmically repeating, iconic relationship.

The questions snowball into increasingly absurd versions of themselves: which of these depicted worlds is meant to be our own? Do the timelines take place in parallel universes, or do these characters, falling in love repeatedly, time and time again, populate a cycle of reincarnation that continues to spin within a single linear timeline? Perhaps within that linear timeline, so many thousands of years pass from one of these narratives to the next that entire civilizations have risen and subsequently collapsed so that the reincarnation of the immortal beings that we call “Meg Ryan” and “Tom Hanks” never see the material culture of their past civilizations, let alone the ephemera of previous iterations of their relationships. Undisturbed, these bodies find each other again and again, always destined to fall in love, forever. Or do they simply become disembodied, archetypal surrogates for the ideal cis-hetero, white, well-off romance?

These questions apply equally to similar character recurrences across cinematic romance. “Richard Gere” and “Julia Roberts” in Pretty Woman (1990) as well as in Runaway Bride (1999); “Emma Stone” and “Ryan Gosling” in Crazy, Stupid, Love (2010), Gangster Squad (2013), and La La Land (2016); “Keanu Reeves” and “Sandra Bullock” in The Lake House (2006) and Speed (1994); and “Adam Sandler” and “Drew Barrymore” in 50 First Dates (2004), The Wedding Singer (1998), and Blended (2014).

I can speculate on these movies or research the relevant industry relationships within Hollywood at the time of production for each of these films. Some reasonable conclusions we might come to: a working relationship was successful; there was “chemistry”; the market was ripe. As likely as any of these answers might be, none explains what to do with the resulting manufactured landscape: one in which the subjectivity of cinematic narrative replaces any single lived experience. How much "Meg Ryan" is in the glass of water I drank this morning? How much "Tom Hanks" is in an ant? In this, I’m less interested in causes than I am in effects. These images, these stories, and their methods for constructing affect bleed into the world. They become embedded in the shower I take in the morning, in the cereal I eat in the kitchen, in the way I giggle at a joke that a coworker makes.

An audience doesn’t only see the You’ve Got Mail versions of “Tom Hanks” and “Meg Ryan” repeatedly fall in love in replay after replay, we see the “Hanks” and “Ryan” avatars through the filter of spectacle, seeing their first kiss from the vantage point of multiple cameras in multiple universes and rearticulations of their nearly immortal bodies.

0.5

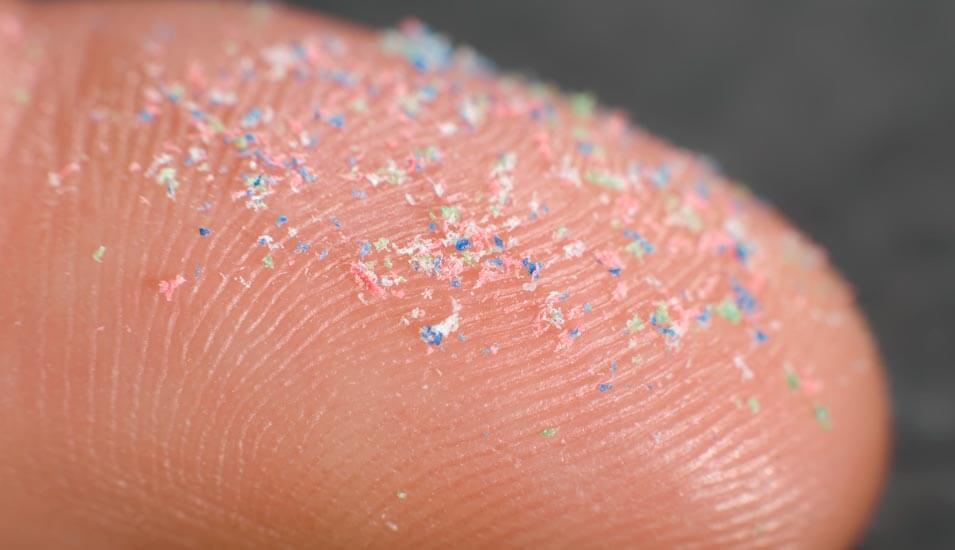

The ways in which these images penetrate contemporary subjectivity are familiar in other, more readily observable fields. One example: the ecological study of plastics that reveals the ways in which this material cycles through an environment, breaks down, and becomes inseparable from the natural world. The classical model might center the production of large, cheap plastic products that get produced using injection molding processes, that then travel to a consumer before later continuing on to a landfill before fragmenting into smaller and smaller shards that go on to circulate through an environment as they disintegrate. The contemporary model of plastic circulation points towards something more ouroboric: the manufacturing of microbeads, which, before their US outlawing in 2015, were produced as microscopic plastic particles (less than one millimeter in their largest dimension) for suspension in high-viscosity skincare treatments and functioned as a mild abrasive/exfoliant that rubbed away at built up oils while scrubbing facial pores. Produced at a scale similar to that of the microplastics that circulate as pollution after the classical manufacturing process, a blur between waste and commodity occurs here.

Much of this process goes unobserved, but it is possible to point to some sort of anonymous start point and end point----poly-products are manufactured and then end up everywhere, permeating all natural and manufactured material at a microscopic level. More recent microbead models of production insert new material on a scale most familiar as pollution. These products more immediately transition between market shelf and ecosystem. But consumers operate within this ecosystem: two recent New York Times pieces cite studies that show that microplastics have recently been observed both in the human gut (in a pilot study with a small sample size) as well as in the air. Brief headlines about a trash island in the Pacific used to elicit feelings of guilt, but now they bring about feelings of empathy since I am partially composed of microplastics, as well. I continue to consume them; I shit them out, too.

The presence of microplastics in both the broader environment as well as in the subjects that consume them indicates a dynamic of simultaneous ubiquity and invisibility familiar to that in a landscape of cinema and its byproducts. As subjects become constructed by this material, they secrete it as waste, through the methods in which they frame experience, through the cinematic canons that anchor their lived experience, in the shared references through which they identify cultural kin. These microplastics exist in the gut as accidental consumptions of the same material that might be used for certain prosthetics such as glasses and prosthetic legs (which later become waste and breakdown into microplastics which may be consumed later by a different subject). This breakdown process in which objects steadily increase in entropy is recognizable on a celestial level, but the feedback loop in which that process takes places becomes more specific to culture and microplastics.

1.5

At an international summit held in Singapore between North Korea and the US in June 2018, President Donald Trump presented to Chairman Kim Jong Un an untitled film. The four minute video was a simulation of a movie trailer; it employed the refined aesthetic language of an overly earnest action-drama movie. In this recognizable visual language and structure, a montage cuts between scenes of industry, people, performances, cultural events, and workplaces in a method that recalls the 1982 experimental and eco-minded film Koyaanisqatsi, but with the overlay of a dramatic voice actor on top of its universalized imagery contrasted with the insertion of various military images as warning. The film itself, reflecting on the peace talks between the two countries, ends on a cliffhanger, “One moment; one choice; what if...the future remains to be written?”

Though the film is credited to a production company titled “Destiny Pictures,” Garrett Marquis, a representative from the US National Security Council, explained after the press event that, “The video was created by the National Security Council to help the president demonstrate the benefits of complete denuclearization, and a vision of a peaceful and prosperous Korean peninsula.”